I. Introduction.

This entry will examine ethical issues raised by relying on putting a price on carbon as a policy response to reduce the threat of climate change.

Establishing a price on carbon emissions as a response to reduce a government’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has received strong support around the world. One observer of global climate change policy developments has concluded:

Not only is there a robust consensus among economists, but they have been remarkably successful in spreading the gospel to the wider world as well. Climate activists, wonks, funders, politicians, progressives, and even conservatives (the few who take climate seriously) all sing from the same hymnal. It has become conventional wisdom that a price on carbon is the sine qua non of serious climate policy. (Roberts, 2016)

This article will identify potential ethical problems with relying on carbon pricing to reduce the enormous threat of climate change despite the widespread popularity of pricing carbon regimes. As we shall see, although a few ethicists have ethical problems with any carbon pricing scheme, many others approve of carbon pricing schemes provided that the regime design adequately deals with certain ethical issues that carbon pricing regimes frequently raise.

Climate pricing regimes vary greatly from the government to government and among different types of carbon pricing regimes. However, there are two basic methods for using a price on carbon to reduce greenhouse (GHG) emissions.

The first is to distribute carbon caps, often referred to as carbon allowances, to GHG emitters usually followed by a tightening of the cap over time to achieve desired GHG emissions reduction goals. Those who have more allowances than they need may sell allowances to those who do not have enough. Thus carbon allowances may be bought and sold, a scheme that is often justified by economists by claiming that this approach leads to GHG reductions at the lowest cost thereby finding an efficient solution to climate change while the amount`of GHG emissions achieved by the scheme may be determined by the total amount of allowances permitted. This method is usually referred to as “cap and trade”

Many cap and trade regimes allow those who need additional allowances to reduce GHG emissions to levels required by the cap to fund GHG emissions reduction projects often anywhere in the world including in places without a cap and get credit for the amount of GHG reductions achieved by the funded project, which credit then can be applied to determine whether the cap has been achieved. Different trading regimes have different rules specifying where and under what conditions emissions credits can be obtained by funding projects in other places.

The other common carbon pricing scheme is for government to charge a price for carbon emissions, a method usually referred to as carbon taxing. The carbon tax works also to lower GHG emissions because it makes technologies which produce less GHG per unit of energy more attractive thereby creating strong incentives for energy users to switch to energy technologies which produce less GHG emissions per unit of energy produced. A price on carbon also creates incentives for all those responsible for GHG emissions to do what they can to emit less GHGs, including, for instance, reducing their carbon footprints by driving less, walking more, lowering thermostats in the winter, adding insulation to buildings, etc.

For these reasons, putting a price on carbon emissions as a policy response to human-induced climate change has strong global support particularly among economists.

This article will identify ethical issues created by (a) any carbon pricing scheme, (b) cap and trade regimes, and (c) carbon taxing regimes. This analysis will be followed by several conclusions.

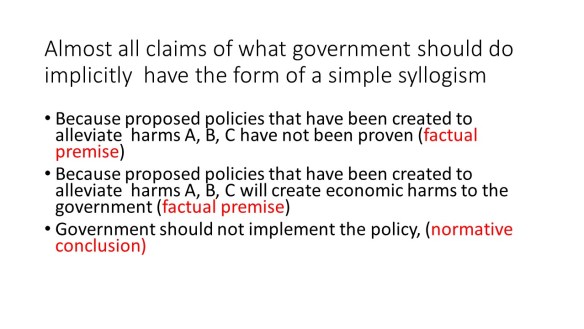

II. Ethical Issues Raised By Any Carbon Pricing Scheme.

Although many ethicists who have identified ethical issues raised by policy responses to climate change that rely on putting a price on carbon acknowledge that pricing schemes have shown to be effective in reducing GHG emissions often at lower costs than other regulatory approaches, some ethicists nonetheless oppose carbon pricing schemes because of certain ethical problems with these schemes. Many other ethicists who acknowledge potential ethical problems with carbon pricing schemes believe these problems can be adequately dealt with by appropriate carbon pricing regime design. Yet even if ethical problems raised by carbon pricing regimes can be averted through carbon pricing regime design, policymakers and citizens need to understand these ethical problems so that they can be mitigated in the design of the carbon pricing scheme.

An ethical approach to climate change would limit GHG emissions by law at levels necessary to prevent human-induced climate change harms to people and ecological systems. For instance, many governments have established legal requirements on the percentage of renewable energy required of electricity providers, a policy response that does no rely on pricing carbon. An ethical approach to climate change is based on different justifications for reducing change harms than some economic approaches. As Vanderhelen said:

An ethical approach to climate policy is based on different assumptions than economic-based policy assumptions. The ethical approach says we should act on climate change now, not because the future costs of inaction exceed those of mitigation, but because the failure to do so harms others. It is our ethical duty to avoid this. (Vanderhelen, 2011)

And so an ethical approach to climate change requires those who are responsible for human-induced climate change harms to comply with their duty to not harm others without regard to the economic value of costs and benefits of climate change policy responses. All national governments in the world have duties to take actions that reduce GHG emissions from their jurisdiction to the nation’s fair share of safe global GHG emissions under the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

In addition, an ethical approach to climate change also identifies ethical issues raised by carbon pricing schemes including the following:

A. Assuring the price will achieve GHG reductions at levels entailed by the government’s ethical obligations.

The amount and speed of GHG emissions reductions that government policies should achieve is fundamentally an ethical question that economic reasoning alone cannot determine. As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded in its 5th Assessment Report:

- How should the burden of mitigating climate change be divided among countries? It raises difficult questions of fairness, and rights, all of which are in the sphere of ethics. (IPCC, 2014, WG III, Ch. 3, pg. 215).

- The methods of economics are limited in what they can do. They are suited to measuring and aggregating the wellbeing of humans, but not in taking account of justice and rights (IPCC, 2014, AR5, WG III, Ch. 3, pg.224).

- What ethical considerations can economics cover satisfactorily? Since the methods of economics are concerned with value, they do not take account of justice and rights in general. (IPCC, 2014,.AR5, WG III, Ch. 3, pg. 225).

- Economics is not well suited to taking into account many other aspects of justice, including compensatory justice (IPCC,2014, AR5, WG III, Ch. 3,pg. 225).

- [I]t is morally proper to allocate burdens associated with our common global climate challenge according to ethical principles. (IPCC, 2014, AR5, WG III, Ch. 4, pg. 317).

Thus, no carbon pricing scheme alone without consideration of ethical issues can determine what the magnitude and timing of a government’s GHG emissions reduction goals should be because a government’s GHG emissions reduction goals must be based on fairness, justice, and obligations to not harm others or the ecological systems on which life depends without the consent of those who will be harmed. These are essentially ethical matters that economic rationality alone cannot deal with. Proponents of carbon pricing schemes claim that pricing regimes allow those responsible for reducing GHG emissions to achieve reductions at the lowest cost, yet the amount of reductions that a nation is obligated to achieve is essentially an ethical matter. So the goal of any pricing scheme should be designed to achieve ethically justified national GHG emissions reduction targets.

All nations in the world have agreed under the 2015 Paris Accord that they are duty bound to adopt policies that will enable the international community to limit warming to between 1.5 degrees C and 2.0 degrees C, the warming limit goal, on the basis of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities in light of national circumstances, the ‘equity’ requirement under the Paris Agreement.(UNFCCC, Paris Agreement, 2015, Art 2.) And so all nations have an ethical duty to determine their GHG emissions reduction goals which at a minimum would limit warming to as close as possible to 1.5 degrees C although no greater than 2.0 degrees C on the basis of what equity requires of it to achieve these warming limits. Equity is understood by philosophers as a synonym for distributive justice.

Although there are differences among ethicists about what equity requires, “equity” may not be construed to mean anything that a nation claims it to mean, such as national economic self-interest. As IPCC said, despite ambiguity about what equity means:

there is a basic set of shared ethical premises and precedents that apply to the climate problem that can facilitate impartial reasoning that can help put bounds on the plausible interpretations of ‘equity’ in the burden sharing context. Even in the absence of a formal, globally agreed burden sharing framework, such principles are important in establishing expectations of what may be reasonably required of different actors. (IPCC, (IPCC, 2014, AR5, WG III, Ch. 4, pg. 317).

The IPCC went on to say that these equity principles can be understood to comprise four key dimensions: responsibility, capacity, equality and the right to sustainable development. (IPCC, 2014, AR5, WG III, Ch. 4, pg 317)

As a result, because some pricing regimes will not reduce national GHG emissions to levels required by their national obligations under the Paris Agreement even those nations that have adopted some kind of carbon pricing regime have had to enact other climate change policies to achieve the nation’s GHG reduction goals. For this reason and because some politicians have conditioned their support for a proposed carbon pricing scheme on acceptance of legal provisions that prohibit policy responses that are in addition to a carbon pricing scheme under consideration by a legislature, policymakers and citizens need to understand that any carbon pricing scheme must assure that a government’s emissions reduction policies will achieve the government’s ethically determined carbon emissions reduction obligations. Thus they must oppose legislation that prohibits a government from supplementing carbon pricing schemes with other laws to reduce GHG emissions.

Thus the quantity of the price placed on carbon under a taxing scheme or the magnitude of allowances under a cap and trade regime should be established after express determination of the government’s ethically prescribed obligations to reduce GHG emissions to its fair share of adequately safe global emissions.

Every national GHG emissions reduction target is implicitly a position on two profound ethical questions among others. They are:

- the amount of warming and associated harms the nation is willing to inflict on others including poor vulnerable people and nations, Since all nations have agreed under the Paris Agreement to limit warming to as close as possible to 1.5 degrees C and no greater than 2.0 degrees C, these warming limits should be the default assumptions of governments’ GHG reduction target formulation;

- the nation’s fair share of total global GHG emissions that may not be exceeded to keep global warming from exceeding the Paris Agreement’s warming limit goals of 1.5 degrees C to 2.0 degrees C

Thus, to make sense of the acceptability of any carbon pricing scheme, government’s should; (a) identify its GHG reduction target, (b) how the target achieves its GHG emissions reduction obligations in regard to warming limits and fairness, (c) the date by which the target will be achieved, and (e) the reduction pathway that will achieve the GHG reduction goal.

The date by which the GHG reductions will be achieved is ethically relevant because any delay in achieving required reductions affects the remaining carbon budget that is available to assure that any warming limit goal is achieved. Carbon budgets that must constrain global GHG emissions to achieve any warming limit goal such as the 1.5 degrees C to 2.0 degrees C warming limit goals under the Paris Agreement continue to shrink until total GHG emissions are reduced to levels that will stabilize atmospheric GHG concentrations at levels that will not cause warming greater than the warming limit goal. Therefore both the magnitude of the government’s GHG emissions reduction goals and the time it takes to achieve the goal are relevant factors in regard to whether any government will achieve GHG reductions that represent its fair share of safe global emissions. In fact the reduction pathway by which the reduction goal will be achieved is also relevant to whether a government will reduce its GHG emissions to levels required of it by its obligations because pathways which produce rapid reductions early in any period will consume less of a shrinking carbon budget than pathways that achieve most of the reductions at later times in the relevant period. This fact is depicted in this chart.

This chart demonstrates that different GHG reduction pathways may consume different amounts of any relevant carbon budget even if the percent amount of reductions, in this case, 100% reduction by 2050, is the same for the different pathways. The amount of the budget consumed by the two pathways is represented by the areas underneath the curves.

B. Intrinsic Ethical Problems With Any Carbon Pricing Scheme.

A few ethicists argue that relying on putting a price on carbon to achieve a government’s obligations is ethically problematic without regard to the details of the pricing scheme.

Ethicist Michael Sandel, for instance, in a 1967 OpEd in the New York Times entitled It’s Immoral to Buy the Right to Pollute identified the following ethical problems with pricing carbon after acknowledging that trading GHG emissions allowances could make compliance for the United States cheaper and less painful. (Sandel, 1967)

Turning pollution into a commodity to be bought and sold removes the moral stigma that is properly associated with it. If a company is fined by a government for spewing excessive pollutants into the air, the government conveys its judgment that the polluter has done something wrong. A fee, on the other hand, makes pollution just another cost of doing business, like wages, benefits, and rent. (Sandel, 1967)

The distinction between a fine and a fee for despoiling the environment is not one we should give up too easily. Suppose there was a $100 fine for throwing a beer can into the Grand Canyon, and a wealthy hiker decided to pay $100 for the convenience. Would there be nothing wrong with his treating the fine as if it were simply an expensive dumping charge?

Or consider the fine for parking in a place reserved for the disabled. If a busy contractor needs to park near his building site and is willing to pay the fine, is there nothing wrong with his treating that space as an expensive parking lot?

In effacing the distinction between a fine and a fee, emission trading is like a recent proposal to open carpool lanes on Los Angeles freeways to drivers without passengers who are willing to pay a fee. Such drivers are now fined for slipping into carpool lanes; under the market proposal, they would enjoy a quicker commute without opprobrium. (Sandel, 1967)

Some human behavior is so morally reprehensible that charging a price for the behavior to create a disincentive is widely seen as morally unacceptable. For instance, most societies would agree that a strategy to reduce child prostitution that relies on increasing the price of child prostitution or taxing a sexual transaction in which children are involved is morally unacceptable. Because some countries’ GHG emissions are far greater than any reasonable determination of their fair share of safe global emissions and these GHG emissions are already contributing to the killing or harming millions of people around the world while threatening tens of millions of others, allowing GHG emitters to continue to emit GHGs at unsafe levels if they are willing to pay the price required by a government rather then establishing a legally determined maximum emissions rate consistent with the emitter’s morally determined emissions limits can be argued to be as morally unacceptable as dealing with child prostitution by imposing a tax. Even though a tax might achieve the same amount of reductions as a legal limit implemented by an enforceable cap on GHG emissions amounts, applying a tax implicitly signals that it is morally permissible to continue emitting GHGs at current levels as long as the carbon tax is paid. Thus, the tax can diminish the moral stigma entailed by status quo levels of emissions.

Putting a price on carbon as a policy response to climate change is often justified by economists as a way to make sure that market transactions consider the value of harms caused by climate change that are unpriced in market transactions. For instance, because the price of coal does not consider the value of the harms caused by the burning of coal that will be experienced by some people who are not participants in the sale of the coal, putting a price on carbon equivalent to the value of the harms caused by the burning of coal is a way of assuring that the value of the harms caused by the coal are considered in the market transaction. This addition to the price is referred to as a Pigovian tax or a tax on any market transaction that generates negative externalities, so that the value of the negative externalities is included in the market price. Most economists recommend that the amount of the tax be based on the social cost of the negative externalities where the social costs are measured in dollars or other monetary units determined by the amount people would be willing to pay to prevent the harm. Once the cost the harms is determined and included in a tax, the market will be able to operate efficiently.

Economists thus justify a tax set in this way because it enables the market to maximize preferences. But ethics is interested not in maximizing preferences people have but in assuring that people’s preferences are those that people should have morally. For ethicists, it is wrong to harm people without their consent, even if those causing the harm could pay victims money calculated by the market value of the harm. That is, according to most ethicists it is morally wrong to harm people or the ecological systems on which life depends even if those causing the harm are willing to compensate those harmed. Some ethicists therefore argue, putting a price on carbon as a policy response to climate change does not pass ethical scrutiny unless the price prevents all non-trivial harms to life, health, and ecological property that people have not consented to. Given that some human rights have already been demonstrated to be violated by climate change (UNHR, 2018), any price on carbon that allows human rights violations to continue does not pass ethical scrutiny.

And so putting a price on carbon does not pass ethical scrutiny as long as the price does not prevent the harms that people have right to object to without their consent.

Although the money from the carbon tax could be used to compensate people for harms caused by climate change, this potential use of the tax revenues does not ethically justify continuing the behavior which causes serious harms to others without the consent of those who are harmed. In addition, because those being harmed by GHG emissions are people all around the world, if the revenue from a tax is to be used to compensate those who will be harmed by the GHG emission, the revenues from a tax would have to be distributed worldwide. At this time there is no such global revenue stream from national carbon pricing schemes.

Many citizens and institutions around the world including many colleges and universities have significantly reduced their carbon footprint because they believed they had a moral obligation to do so as long as their GHG emissions could contribute to harming people, animals, ecological systems on which life depends, or things of great value to people. A sense of moral obligation, without doubt, motivates, at least some people and institutions, to do the right thing. Yet pricing carbon as a response to climate change does not create a legal prohibition to reduce GHG emissions but only an economic incentive to do so. A government could always legally prohibit activities that create GHG emissions that create harms, an approach to changing behavior that was the dominant strategy in environmental law for many decades. Economists, however, have often objected to these “command and control’ approaches because they claim that market-based mechanisms can achieve needed reductions in a more efficient economic way, that is, at a price that includes consideration of the value of the harms created.

At least in the United States, many of the proponents of carbon pricing are failing to educate civil society about the moral obligations of all nations and people to reduce GHG emissions to their fair share of safe global emissions, a concern particularly in light of the very limited time left to limit warming to non-catastrophic levels. These proponents often passionately advocate for the adoption of a carbon pricing scheme because they are accurately convinced that a price on carbon will reduce GHG emissions, yet ignore discussing the non-discretionary moral duty to reduce GHG emissions thus inadvertently leaving the impression that provided that those who are willing to pay a price placed on carbon they have no moral obligation to cease activities which are responsible for carbon emissions.

Economists often justify their market-based solutions as a method for maximizing the enjoyment of human preferences. They thus calculate the value of harms avoided by climate policies by determining a market value of the harm and if there is no market value they often determine the value of the harms by determining what people are willing to pay to prevent the harm. This allows the economists to compare the cost of reducing GHG emissions against the value of harms prevented through pricing and in so doing allows a policymaker to select a policy option which maximizes human preferences. Yet, as we have seen ethics is concerned not solely with efficiently achieving the preferences people have but with establishing what preferences people should have in light of their moral obligations.

Under an ethical approach to climate change based on an injunction against harming others, because any additional GHG are raising GHG atmospheric levels which are already increasing harms people are suffering from droughts, floods, intense storms, tropical storms, and heat waves among other causes of climate-induced harms, an ethical argument can be made that any carbon pricing scheme should seek to achieve the lowest feasible GHG emissions levels as quickly as possible. Ethics refuses to define what is ‘feasible’ in terms of the balance of costs and benefits. Ethics requires that harm to innocent victims must be avoided, even when the cost of reducing pollution exceeds the monetary value of harms to life and ecological systems on which life depends. Not all economists, of course, argue that government policies should be based on cost-benefit analysis but many do.

An ethical approach to climate change also requires that polluters should pay for the harms and damages they create as well as the costs to them of reducing the pollution. Many carbon pricing schemes ignore the duty of GHG emitters to compensate those who have been harmed by their GHG emissions and base the amount of the tax on the amount of money needed to reduce GHG emissions while ignoring any obligations to compensate those who have been harmed by their emissions. This problem could be remedied by basing any price on the amount of money needed to compensate those who have experienced loses and damages or by providing separate funds to compensate those who are harmed by climate change but most carbon pricing schemes fail to take these matters into consideration.

Ethicists also acknowledge that climate-related harms are more likely to affect the poor, not just those who are now being asked to contribute toward its mitigation. For this reason, many ethicists prefer laws that prohibit certain immoral behaviors over laws that allow people to continue their immoral behavior if they are willing to pay higher prices entailed by the value of the harms caused by their behavior.

Economists often support pricing schemes if the pricing leads to the market incentivizing the use of alternative technologies that don’t create the harms of concern. In such cases, the morality of the pricing scheme likely depends on whether the technical transformation created by the pricing scheme will take place soon enough to prevent the harms of concern.

However, even in these cases, many ethicists believe that human activities that create morally unacceptable levels of GHG emissions should be responded to as moral obligations and only support pricing schemes so long as the scheme will enable reducing GHG emissions to morally acceptable levels as rapidly as possible. However, even so, some ethicists warn against erasing the moral stigma entailed by morally unacceptable levels of GHG emissions that could occur by allowing some to continue to exceed their moral obligations if they are willing to pay to do so.

Pope Francis in Laudato Si, the papal encyclical released in July 2015, questions whether market capitalism can effectively protect the poor, and in one passage specifically criticized “the strategy of buying and selling ‘carbon credits.’ More specifically Laudato Si argues that:

The strategy of buying and selling ‘carbon credits’ can lead to a new form of speculation which would not help reduce the emission of polluting gases worldwide. This system seems to provide a quick and easy solution under the guise of a certain commitment to the environment, but in no way does it allow for the radical change which present circumstances require. Rather, it may simply become a ploy which permits maintaining the excessive consumption of some countries and sectors. (Laudato Si 171).

The Pope’s objection appears to be based in part on the fact that a carbon pricing scheme will allow those who can afford to continue emitting GHGs after paying the pricing fee to do so while those that are unable to afford to pay the fee will need to reduce the activities that create GHG emissions. Yet this problem can be somewhat ameliorated by carbon pricing regime design decisions on how revenues are distributed or how allowances to emit are allocated. However, these decisions raise questions of distributive justice, that is questions about how burdens or benefits of public policy should be allocated to comply with what fairness requires. For this reason, carbon pricing schemes often raise serious questions of distributive justice.

In addition if revenues from pricing schemes are to be used to help compensate those who are most harmed by climate change, given that those who are most harmed are often very poor people in poor nations that usually have done little to cause climate change, the revenues would need to transferred to poor nations and people around the world. Yet no national carbon pricing schemes have yet proposed such international financial transfers.

III. Ethical Issues Raised by Cap and Trade GHG Emissions Reduction Schemes

This paper next examines the following ethical issues raised by cap and trade regimes that are additional to those discussed in Section II.

A very detailed examination of some ethical issues raised by cap and trade regimes by Simone Carey and Cameron Hepburn is entitled Carbon Trading: Unethical, Unjust, and Ineffective? The Carey/Hepburn paper discusses in detail the following ethical issues raised by cap and trade regimes that are in addition to those discussed above. The following is a summary of issues discussed by the Carey/Hepburn paper.

A. Rights to use nature cannot be owned

Because GHG emitters that receive allowances or buy allowances from those that have excess allowances could under some trading mechanisms hold or bank these allowances, holders of allowances could be understood under some trading schemes to have a right pollute the atmosphere at levels entailed by the allowances they hold. However, most ethicists believe that no one should have a property right to pollute the atmosphere. Because in absence of a rule that would prevent the owner of allowances to bank the allowances for use far into the future, the owners of the allowances could accumulate the right to pollute far into the future. As a result, some ethicists have argued that allowances should be limited to a specific time period and be understood to be revocable if the science changes and concludes that greater reductions are necessary then those that were understood to be necessary to prevent harm when the allowances were distributed.

B Responsibilities to abate harms cannot be transferred to others

Some ethicists believe that some human responsibilities should not be allowed to be transferred to others. For instance, it is generally believed to be ethically unacceptable for those who are potentially subject to being drafted into the military to be able to buy their way out of this obligation by paying someone else to agree to take one’s place if he or she is drafted. For this reason, some ethicists claim that is ethically problematic for high GHG emitters to get a credit for reductions made by others while not requiring more of the high emitters to reduce their emissions.

C. Distributive justice issues with how allowances and revenues are allocated

Because those with the money to do so can buy scarce allowances, participants in a cap and trade regime can wind up with vastly unequal levels of allowances creating significant differences among participants in rights to emit GHGs. In addition, because rules determining who can get allowances and what is done with the money generated from allowance trading can create great imbalances, rules for allocating allowances and revenues from sales of allowances should be consistent with what distributive justice requires to assure fair burden and benefit sharing. Distributive justice requires that people should be treated equally unless there are morally relevant reasons for treating people differently. There is no reason in principle for allowance and revenue allocations to lead to a more unequal distribution of wealth. It will depend on how the cap and trade scheme is designed.

These issues are discussed in more detail by the Carey/Hepburn paper.

D. Ethical issues created by the fact that some cap and trade regimes allow high emitters of GHGs to count emissions reductions made by projects of others funded by the emitters in achieving the high emitters’ GHG reduction obligations.

Some cap and trade regimes allow those with GHG emissions reduction obligations to count the reduction of GHG emissions made by others’ projects funded by the emitter as a credit in achieving the emitter’s cap obligations. Economists justify this feature of cap and trade because it allows emitters to achieve GHG reductions at a lower price, However, not all GHG reduction strategies will reduce GHG emissions with equal probabilities that GHG reductions made by the emitter would actually have achieved. For instance, an electricity supplier can commit to reducing its emissions to amounts that will be achieved with high levels of confidence by installing non-fossil energy but if the electricity supplier relies on funding a forestation project in a third world country to obtain a credit for its emissions reductions. the actual reductions to be achieved by the funded project are much more speculative because of problems in assuring that any forest project will keep GHG reductions achieved by photosynthesis of the forest out of the atmosphere forever. Thus funding a project to achieve GHG emissions credits raises issues about the reliability of achieving specific GHG emission reduction amounts that are more reliable if the person responsible for GHG emissions must assure that GHG emissions will actually be achieved.

Thus cap and trade regimes often also raise the following ethical problems which were discussed in more detail in a prior entry on this website. (Brown, Ethical Issues Raised By Carbon Trading, 2010).:

a. Permanence. Many proposed projects for carbon trading raise serious questions about whether the carbon reduced by a project will stay out of the atmosphere forever. Yet permanent storage of carbon is needed to assure equivalence between emissions reductions avoided if no credits were issued and atmospheric carbon reductions attributable to a project which creates carbon credits. This is so because emissions reductions should guarantee that some quantity of GHG will not wind up in the atmosphere, yet some projects which are used to substitute for emissions reductions at a source have difficulty in demonstrating that the quantities of carbon reductions projected will actually be achieved. For instance, carbon stored in forests, soils, or geological carbon sequestration projects could be released to the atmosphere under the certain conditions. For example, rapid temperature change could kill trees thus releasing back into the atmosphere carbon stored in the trees. This problem is usually referred to as the problem of “permanence” of carbon reduction projects. For this reason, only projects that assure permanent reduction of carbon in the atmosphere can be categorized as environmentally effective projects and should be used to offset activities which actually release carbon.

b. Leakage. Many proposed projects for carbon trading raise serious questions about whether carbon reduced by a project at one location will result in actual reductions in emissions because the activity which is the subject of the trade could be resumed at another location. For example, paying people to plant trees in location A is not environmentally effective if these same people that receive the money chop down trees at place B. This is the problem usually referred to as “leakage.” Forest and other kinds of bio-sequestration projects that sequester carbon in particular often create leakage challenges. Industrial projects can also create leakage problems if the industry gets credit for reducing carbon at one industrial plant while moving the carbon producing activities to another place. If leakage occurs, then the trade is not environmentally effective.

c. Additionality. Getting a credit for a project which is used in a trade will also not be environmentally effective if the project would have happened anyway for other reasons. This is so because trading regimes usually assume that a GHG emitter should get credit because of their willingness to invest in projects that reduce carbon emissions that would not happen without the incentive to get credit for carbon reductions. If the project would happen without the investment of the emitter, then the investment in the project is not “additional” to business as usual. This is the problem usually referred to as the “additionality” problem.

d. Enforcement of trading regime. A trading regime is environmentally ineffective if its conditions cannot be enforced. Although enforcement of trading regimes is sometimes practical when the project on which the trade is based is within the jurisdiction of the government issuing the allowances, enforcement is particularly challenging when the project is located outside of allowance issuing government. In such cases, enforcement must be “out-sourced” to other institutions or governments In addition, while many hundreds of millions of dollars are being invested in setting up emissions trading schemes all over the world, virtually no resources are being channeled into their enforcement or verification. Although most cap and trade regimes have built-in carbon reduction verification steps, verification remains extremely difficult for many types of carbon reduction projects for which credits are being issued because of the lack of enforcement or long-term verification potential. This enforcement challenge is exacerbated when projects for which credits are issued are in poor countries without the technical capability to enforce or verify that reductions have been made. Because of this, a strong case can be made that those who desire to rely on projects that have dubious enforcement and verification potential should have the burden of demonstrating enforcement and verification potential before they may obtain credits generated from these projects.

e. Distributive justice and internal allocation of a government-wide cap. How a cap is allocated among entities within a government creates many potential distributive justice problems. Governments sometimes distribute a cap they have by giving away allowances, auctioning allowances, and other ad hoc considerations that often take into account political feasibility. Each of these methods of distributing a cap raises distributive justice issues that are often ignored for political reasons. For instance, both auctioning allowances and giving away allowances could be significantly regressive, making higher-income households better off while making lower-income households worse off. Auctioning could also be regressive if the most wealthy get the most permits forcing those without the financial resources into non-polluting options. Sometimes governments choose to allocate the cap by placing caps on “upstream” carbon users such as coal and petroleum companies and ignoring “downstream” carbon emitters such as coal-fired industrial users. A decision to place a cap upstream makes the climate change regime easier to administer but could have regressive effects on those least able to afford increased fuel costs. An upstream cap also can create little incentives for those who can afford to waste energy to change behavior. In contrast, downstream caps puts the responsibility on energy users. There is no ethically neutral way to decide these design questions.

f. Distributive justice and revenue from allowances. When allowances are auctioned or otherwise purchased, governments must make decisions about how to use allowance revenues. These decisions raise a host of distributive justice issues that are often ignored for political reasons. Some governments have chosen, for instance, to use allowance revenues to fund climate change technology research, to meet international obligations to fund climate change adaptation projects in developing countries, to fund programs to reduce deforestation projects in developing countries, to buy off politically powerful opponents to climate change legislation, to help those least able to cope with rising energy costs, or to subsidize nuclear power, geologic carbon sequestration, or renewable energy. Thus, decisions about how to allocate revenues from distributing allowances raise distributive justice issue

IV. Ethical Issues With Carbon Taxes.

In addition to the ethical issues that apply to all carbon pricing regimes identified in section II of this entry, carbon taxing regimes can raise the following additional ethical issues.

a. Distributive Justice and a Carbon Tax. Carbon taxing regimes must decide who must pay the tax and just as is the case for cap and trade regimes in the allocation of allowances, taxing schemes may choose to apply the tax either to upstream producers of carbon fuels such as petroleum or coal companies that distribute fossil fuels or further downstream to entities such as electricity generators who consume the fossil fuels. Upstream taxation creates fewer taxable entities who have a huge tax burden. Therefore the decision on who to tax creates different winners and losers, an outcome which has political significance particularly in places where fossil energy is mostly produced. If the tax is based on the amount of CO2 per unit of energy, then some fossil fuel industries such as coal production will pay a much higher tax per unit of energy, a fact which most greatly affects those places and communities that produce fuels with higher CO2 emissions levels per unit of energy. This fact creates heavy burdens from the tax for those who are dependent on the sale of fuel with higher CO2 production levels. And so a decision about who must pay a tax has distributive justice implications.

How the tax revenues are used by the government also has enormous political and distributive justice implications. Policymakers are faced with many competing ways of using tax revenues generated by putting a price on carbon. Many parts of the world that have established a carbon tax use it primarily to subsidize technologies that produce lower amounts of GHG per unit of energy such as wind and solar power. Other governments use the revenues to ease the burden on those who are most affected by the tax, including poor people. Thus how the revenues of a carbon tax are distributed raises deep questions of distributive justice which also create issues of political feasibility.

b. Amount of the tax.

As we have seen all carbon pricing schemes raise ethical issues about whether the price is sufficient to achieve GHG emissions reductions consistent with the government’s ethically determined obligations to reduce GHG emissions. A pricing regime that is based on taxing carbon emissions raises more challenging questions about whether the tax is ethically stringent enough than cap and trade regimes because governments are able more easily assure that the cap is stringent enough than a regime based on taxing carbon because the size of the cap may be set directly on the magnitude of GHG reductions required for the government to achieve its ethically determined GHG emissions reductions obligations while the sufficiency of a tax must rely on economic modelling to determine the magnitude of reductions that will be achieved by different levels of the tax. Determining the amount GHG reductions that will be achieved by different levels of the tax is always somewhat of a guessing game due to the inherent imprecision of economic modeling to predict how entities and people will respond to different price signals. For this reason, taxing schemes that seek to assure that the government will reduce GHG emissions reductions levels congruent with the government’s ethically determined reduction obligations should include accelerator provisions that would increase the amount of the tax once it is determined that actual GHG reductions are not consistent with reductions pathways required to achieve ethically determined reductions obligations. However, because experience with carbon taxing programs around the world has demonstrated that political backlash will likely arise that undermines government support for continuing a carbon tax that is judged to be too high, governments which seriously seek to reduce their GHG emissions through imposing a tax alone may need to consider back up strategies rather than rapidly accelerating taxes if the original tax does not achieve the GHG reductions required of it by its ethical obligations.

c. Considering responsibility for prior emissions, an issue relevant to distributive justice.

Distributive justice supports an allocation of burden sharing obligations on the basis of who is most responsible for causing the current problem. Carbon tax regimes are usually forward-looking; in that most schemes make everyone pay the same price for using the atmosphere’s capacity to absorb CO2. Thus the scheme ignores responsibility determined by looking backward at questions such as:

- Who caused the problem?

- Who benefited from past emissions?

- Who is in the best position to fix the problem?

To deal with these questions, a carbon tax may need to be supplemented by additional policies, for example by tax credits for poor people or sharing of tax revenues with those who must pay the tax but who have done little to cause the current problem so that the tax scheme can consider the distributive justice implications of looking backward at who is most responsible for the current problem

V. Conclusions.

As we have seen carbon pricing schemes designed to reduce GHG emissions raise a host of ethical issues and problems.

Although many of these ethical problems can be dealt with by the pricing carbon regime design, given the enormous threat to life and ecological systems created by human-induced climate change, perhaps the most important ethical issue raised by carbon pricing regime is whether the carbon pricing regime will be successful in reducing a government’s GHG emissions to its fair share of safe global emissions.

Because there is limited political support for enacting carbon pricing schemes with sufficient pricing levels to achieve the enormous reductions in GHG emissions now necessary to prevent very dangerous climate change, carbon pricing schemes will likely require policy responses in addition to carbon pricing alone.

Because of the need to judge whether any carbon pricing scheme will achieve a government’s ethically determined GHG emissions reduction obligations, all proposed carbon pricing schemes should be clear and transparent on how the pricing scheme will achieve the government’s ethically determined GHG reduction goals. A pricing scheme could contribute to achieving a nation’s GHG reduction obligations either by establishing a price that will sufficiently reduce a government’s GHG emissions to achieve the nation’s GHG reduction obligations by itself or in combination with other GHG reduction policies. However, to judge the adequacy of the pricing scheme, governments should explain the role of any carbon pricing scheme in achieving its ethically determined GHG reduction obligations.

References:

Brown, D. (2010, Ethical Issues Raised By Carbon Trading; https://ethicsandclimate.org/2010/06/15/ethical_issues_raised_by_carbon_cap_and_trade_regimes/

Carey, S.& C.Hepburn, (2011) Carbon trading: unethical, unjust and ineffective? http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/WP49_carbon-trading-caney-hepburn.pdf

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 1995, AR2, Working Group III, Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change, https://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/publications_and_data_reports.shtml#1

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2014, Working Group III, Mitigation of Climate Change, http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/

Pope Francis, (2015), Laudato Si http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html

Roberts, D. (2016) Putting a price on carbon is a fine idea. It’s not the end-all be-all, Vox, https://www.vox.com/2016/4/22/11446232/price-on-carbon-fine.

Sandel, M. (1967) It’s Immoral to Buy the Right to Pollute, http//www.nytimes.com/1997/12/15/opinion/it-s-immoral-to-buy-the-right-to-pollute.html

UNFCCC, Paris Agreement2 (2015), https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf

UNHR, UN High Commissioner on Human Rights, (2018) Climate Change is a Human Rights Issue, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/ClimateChangeHumanRightsIssue.aspx

By:

Donald A. Brown

Scholar in Residence, Professor

Widener University Commonwealth Law School

dabrown57@gmail.com

COMMENTS

The following comments on this entry were made by Eric Haites, an economic consultant for Margaree Consultants Inc, in Toronto

Ethical Issues Entailed by Pricing Carbon as a Policy Response to Climate Change confuses benefit-cost analysis with carbon pricing and criticizes carbon pricing on grounds that also apply to non-price policies.

Carbon pricing policies – cap and trade systems (CTSs) and carbon taxes – are regulatory measures to limit greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) by specified sources within a jurisdiction. They may be implemented in conjunction with or as substitutes for non-price regulations such as subsidies for non-carbon energy, minimum gasoline efficiency standards for vehicles, funding for affordable public transportation, requirements/incentives to increase the supply of renewable energy and energy efficiency standards for buildings.

Benefit-cost analysis of climate change compares the estimated costs of different levels of global emissions reductions with the estimated value of reduced global climate change damages associated with those emission reductions. Benefit-cost analysis of climate change is extremely complex conceptually and in practice. Since the analysis must span a century or more due to the long atmospheric lives of greenhouse gases, the calculations are very sensitive to the discount rate and have large uncertainty ranges.

A CTS or carbon tax can be implemented by a jurisdiction to help achieve its GHG reduction goal regardless of how that goal is established. A country that has a nationally determined contribution under the Paris Agreement can use carbon pricing and/or non-price policies to meet its commitment.

It is true that many economics textbooks suggest that the carbon tax be set at the level determined by benefit-cost analysis, but that is not necessary and is based on the implicit assumption that an emissions reduction goal has not been established by other means, such as international negotiations.

Many of the criticisms of carbon pricing policies do not specify an alternative policy. If emissions are to be reduced, the alternative is a set of non-price regulations including efficiency standards and increased reliance on renewable energy. In practice, neither carbon pricing nor non-price regulations cover all GHG emissions, so there are regulated emissions and exempt emissions under every policy.

Consider then the claim that it is immoral to buy the right to pollute. Before a regulation is implemented, the right to pollute in unlimited quantities is free. Regulations impose costs and/or quantity limits on the right to pollute. In the case of a carbon tax, there is a cost for each ton of GHGs emitted by specified sources. In the case of a CTS, total emissions by specified sources are capped. In the case of non-price regulations there is a compliance cost, but any remaining emissions are free and unrestricted. The cost of an efficient automobile is higher, but its emissions are not priced or restricted.

One of the arguments by Simone Carey and Cameron Hepburn cited by the paper is that the rights to nature can not be owned. Many CTSs explicitly state that the allowances are not property rights. Almost all of the CTSs have cancelled or greatly devalued surplus allowances.

In the paper, the discussion of the distinction between a fine and a fee is misleading for a CTS. Every CTS has penalties for non-compliance, so the correct comparison is the fine for a CTS and that for a non-price policy. The non-compliance penalty for most CTSs is a reduction in emissions equal to the exceedance plus a penalty. To use the analogy in the paper, a CTS requires the offender to pick up the beer can and pay a penalty. In contrast, a non-price regulation only imposes a fine.

The paper raises the concern that “the tax can diminish the moral stigma entailed by status quo levels of emissions.” Why would the moral stigma associated with residual emissions differ? Are the residual emissions by a source subject to a carbon tax morally less acceptable than those by the owner of a more efficient automobile. Sources subject to carbon pricing policies have a financial incentive to make emission reductions that cost less than the tax/allowance price. Sources subject to non-price policies have no incentive to reduce their emissions.[1]

Issues of distributive justice arise for all regulations; which sources are regulated, how stringent is the regulation, how should groups that are adversely affected by compensated? The paper clearly identifies these issues for CTSs and carbon taxes. But they apply equally to non-price regulations. Who pays for the more efficient vehicles and buildings, the public transit and the additional renewable energy? Those costs will be borne by specific groups or the government. Carbon pricing policies have the advantage that they generate revenue that can be used to help address distributive justice.

The paper argues that past emissions should be considered when addressing distributive justice. Presumably, this consideration applies to any policy, not just carbon pricing. In practice the ability to do this is limited due to lack of data and the long atmospheric lives of GHGs. Non-price regulations often differentiate between existing and new sources and CTSs address this concern through their allowance allocations.

In summary, carbon pricing can be implemented by a government to help meet its GHG emissions reduction target regardless of how that target is established. A CTS or carbon tax can be implemented alone, jointly or in combination with non-price policies. In practice all jurisdictions with a pricing policy also implement non-price policies. Many of the ethical criticisms of pricing policies apply to non-price policies as well. Price policies have the advantage of raising revenue that can be used to address distributive justice.

[1] Indeed, they may have a financial incentive to increase emissions. A more efficient vehicle may have a lower operating cost per km so the owner may drive more.

Resonse to comments

I agree that levels of GHG reductions achieved by a pricing scheme need not be determined by Cost-Benefit Analysis although some economists recommend this. In such cases the ethical issues discussed in this paper apply

Mr, Haite is correct that the articles criticism of carbon pricing schemes may also apply to other responses to climate change, However, if the level of reductions that constitute a nation’s GHG reduction target are based on a nation;s ethical obligations, then the problem entailed by some carbon pricing scheme’s allowing emitters to continue emit as long as they pay a tax is not possible.